This is the seventh of twelve posts in the Exploring Mindfulness blog series, a reflection on the book When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön. This post addresses Chapters Eleven and Twelve. Participants are encouraged to practice mindful meditation daily throughout the twelve weeks, even if for five minutes at a time. (7.5 min read)

Before addressing Chapters Eleven and Twelve, I want to briefly explain two concepts that are in implied but not addressed directly in When Things Fall Apart:

Māyā refers to the illusions that keep us from seeing the world as it really is. This is one of the leading causes of human suffering. In Indian mythology, Māyā is personified as a god or demon with the power to trick us with illusions. Māyā is a fundamental concept of Buddhist psychology akin to the idea of “faulty thinking” in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mindfulness is a practice for dissolving māyā by observing emotions and thoughts as they appear and disappear.

Dualistic Mind is the typical way we see the world. Richard Rohr, a Christian contemplative, explains it well:

The dualistic mind is essentially binary, either/or thinking. It knows, by comparison, opposition, and differentiation. It uses descriptive words like good/evil, pretty/ugly, smart/stupid, not realizing there may be a hundred degrees between the two ends of each spectrum. Dualistic thinking works well for the sake of simplification and conversation, but not for the sake of truth or the immense subtlety of actual personal experience. *

A non-dualistic mind is one of the fruits of mindfulness. Dualism is a form of māyā. One type of dualistic thinking is self/other. In the ancient Indian philosophy from which the Buddha emerged, there is not a “self” or an “other.” There is only “oneness.” This is described as the “Self” with a capital “S”. That is why, for example, self-compassion is necessary in order to have compassion for others and vice versa. In Eastern thinking, our natural state is oneness, so our natural state of mind is non-dualistic. A newborn does not have a sense of being separate. But we are raised in a dualistic culture, so as we grow, we develop an ego—the sense of “I,” which implicitly creates the sense of a separate “other.” As such, we are conditioned into the illusion of separateness. Mindfulness is, then, a practice for returning to our natural state of mind.

~*~

The Awakening

As the story goes, the Buddha-to-be, sat under the Bodhi (Awakening) tree, crossed his legs and faced east. Through many thousands of lives of practices and setbacks, he reaches this moment where he states,

Let my skin, sinews, and bones become dry… and let all the flesh and blood of my body dry up, but never will I stir until I have attained the supreme and absolute wisdom! **

As he sat, he was visited by the demon, Mara, and his entourage. They came to block his awakening. Among the entourage was Mara’s sons, Mental-Confusion, Gaiety, and Pride. Mara’s daughters appeared before the Buddha-to-be as well. They were Lust, Delight, and Pining. He was not moved.

Next, Mara chastened him for dereliction of his princely duties, but the Buddha-to-be sat unmoved.

Mara let fly an arrow that had “set the sun aflame,” yet it failed to penetrate, and the Buddha-to-be sat unmoved.

Desperate now, Mara, the Lord of Death, called forth an army of monstrous demons. The Buddha-to-be simply bade Mara put aside malice and go in peace, and remained unmoved. Mara retreated and the Buddha-to-be sat through the night, and as the sun appeared in the spot that he’d been facing, he awoke. He became the Buddha, which means the Awakened One.

This grand story can be seen as a metaphor of our inward journey. The thousands of lives represent the meditation we do day after day. The Mental-Confusion, Lust, and other siblings, the call to duty, the sharp point of the arrow, and the army of demons led by Death are metaphors for all the emotions and thoughts that arise in meditation. It is not a story of the past. The Buddha known to history is not the only Buddha; the Buddha is not a god. As Pema puts it,

When we discover the Buddha that we are, we realize that everything and everyone is Buddha. We discover that everything is awake, and everyone is awake.

Any tree you sit under to meditate is the Bodhi-tree. The living room couch, when you sit there to meditate, is the Bodhi-couch. And Mara will appear to you. You may have to deal with mental confusion, lust, and guilt for neglecting duties. You may face each of your many fears, including the fear of death. But they will not hurt you if, when realize you’ve been carried away by them, you bid them go in peace, and simply return to your breath.

Pema describes the teachings about Mara in Chapter Eleven. She writes,

Traditional instructions on the forces of Mara describe the nature of obstacles and the nature of how human beings habitually become confused and lose confidence in our basic wisdom mind.

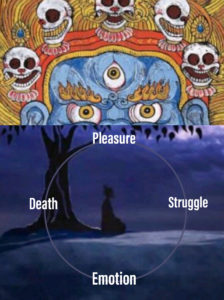

I have created a graphic of the four maras encircling the Buddha-to-be under the Awakening-tree. Above, it is a traditional depiction of Mara.

Inward

Meditation has been referred to, disparagingly, as navel-gazing. Perhaps this is as it appears to an uninformed onlooker. The restful alertness of mindfulness that Pema and others teach quickly debunks such claims. Yet, slipping into escape through self-absorption is a risk and is one of the reasons it is helpful to have guidance through books, classes, and teachers. With that said, an inward focus on how thoughts and emotions arise builds a foundation necessary for authentic relationships with others. As I write about Chapter Twelve, I will focus on the inward aspects of mindfulness. In addressing Chapter 14 in a later post, I will focus on the outward elements.

Chapter Twelve, “Growing up,” encourages us to do inward exploration to let go of our reliance on what the outside world tells us—growing up means to stop waiting for someone else to tell us what to do. It means to stop waiting for someone else to tell us what the truth is. We have to find out for ourselves what is true. This can feel like a lonely and scary process at first, but with a mindful disposition, it can also be exciting—an adventure. Growing up allows one to say, “No one can tell me what is true so that I seek the Truth myself.” To find out for ourselves is to be curious and inquisitive about the nature of things. Perhaps mindfulness could be summed up as: Be inquisitive. Meditation could be summed up as Practice inquisitiveness.

Basic Goodness. Pema Chödrön is a nun in the Shambala tradition of Buddhism that was begun by her teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. An essential tenet of Shambala is “Basic Goodness.” Keep in mind, though, that Buddhism does not have a doctrine or creed. It is personal experimentation to discover the nature of things. As such, the tenet of “Basic Goodness” is not a belief. So it is not technically accurate for one to say, “I believe in Basic Goodness.” It would be more accurate for one to say, “Others, through the practice of mindfulness, have discovered basic goodness in themselves and teach that each of us can discover this within ourselves.” This can inspire us to practice.

Basic Goodness is not thinking of oneself as a “good person.” To think of oneself as a good person implies that there are bad people. That would be dualistic thinking. Secondly, when I think of myself as a good person and, as always happens, I see evidence to the contrary, I feel nagging guilt. I think that I have let myself down. Or I repress that guilt or deny the evidence. Or I may even project the evidence of ways that I am bad onto others, so I see them as bad.

Basic Goodness is not something taught likes manners or something that some have, and others don’t like a good character. It is who we are. We don’t see it because of the illusions of māyā. We can only see our Basic Goodness when we dissolve māyā through mindfulness and other related practices. Unfortunately, we are too often conditioned to forget our Basic Goodness, such as through rewards and punishments, as described in the last post. To practice is a kind of deconditioning.

- We practice openness when our conditioning compels us to close.

- We practice spaciousness when our conditioning forces us to constrict.

- We practice softening and lightening-up when our conditioning suggests hardness and heaviness.

While an arisen Basic Goodness seems like a happy thing, there is a lot of anxiety and discomfort in the process of arising. That is because letting go of dualistic thinking makes us uneasy since we don’t know where we stand. In Chapter Nine, Pema Chödrön described drawing lines and the initial comfort of standing on one side or the other because then we feel that we know where we stand. The reality is that there are no lines—no reference points. This creates discomfort for most of us—even anxiety and fear. This fear is a path to the discovery of Basic Goodness. It takes bravery, and that’s why it is called the path of the warrior. Non-duality—no lines and no reference points can also be described as “groundlessness” as introduced in chapter 6. I imagine the uneasiness of suddenly experiencing zero gravity—weightlessness—and saying to myself, “This is gonna take some getting used to!”

*The Dualistic Mind by Fr. Richard Rohr, OFMSunday, January 29, 2017

**From Jātaka referenced in Oriental Mythology by Joseph Campbell

~~~~~*~~~~~

Exercise:

When you sit to meditate. Settle yourself in for your seated practice. Sit and know that you are sitting. Spend a few moments as you typically practice—have light focus on your breath. When your mind wanders, note it and simply begin again.

- For a moment, think of something in your life that compels you to close down. It can be an ongoing disagreement with a friend, significant other, or a family member. Or perhaps it’s a political view that feels diametrically opposed to your viewpoint or values. Letting down your defenses, letting go of your arguments, imagine your chest opening up to let it in. Imagine being open to being wrong

- Recall, something that makes you shrink in shame or fear. (Note: if you are afraid that you will be triggered, choose a less significant fear or embarrassment). Pay attention to your body. What happens to it when you feel fear or shame? You may feel yourself constrict or grow small. While the threat that initially caused you fear or the action that led to shame may be real, the feelings come and go. Lean into the fear or shame without bracing yourself. Perhaps say to yourself, “This is what fear feels like. This is what shame feels like”.

- Think about a situation that brings up painful emotions in you. Feel the hardness and heaviness of these emotions.

Be aware of how you usually experience these emotions. Now, without denying these emotions, be open to the possibility that they are softer, lighter, and less substantial than they feel.

Thanks for participating!

ॐ I bow to you,

Perry

~~~~~*~~~~~

Next Post on 6/21/20 will focus on Chapter Thirteen

To find out more about the series or to participate in the discussion, go to Welcome to the Exploring Mindfulness Series.